Abstract

This study aimed to investigate the factors that influence WeChat users’ health information-sharing intentions by developing an integrated model drawing upon Social Capital Theory, Social Support Theory, and Theory of Reasoned Action. An online survey was conducted with 353 WeChat users, whose responses were analyzed to get the following outcomes. First, the results indicated that subjective norms and attitudes significantly influence health information sharing intention, which indicated that having a positive attitude towards the information and being influenced by the norms of the group to maintain positive social and interpersonal relationships affect sharing intentions. Secondly, all three dimensions of social capital contributed positively towards developing subjective norms and attitudes. However, trust was found not to considerably impact the health information sharing intention, unlike previous research. These findings provide valuable insights into comprehending health information-sharing behavior and have practical implications for interventions aimed at promoting health information sharing on social media.

Introduction

With the growth of the Internet and advances in information technology, social media has become the most widely used channel for people to generate, access, and share health information (Wallace et al. 2021; Afful-Dadzie et al. 2023). More and more users have accustomed to using social media to share health information with family and friends, including their health status, preventing related diseases, and communicating with their doctors about health activities (Chen and Wang 2021). In China, it is common to use WeChat to view and share health information. It provides integrated functions, in which you can share health information directly to friends and groups, as well as search for health information directly or through Official Public Account, and share information they consider useful in WeChat Moment (Wu and Kuang 2021). A national survey has found that 97.68% of respondents indicated that they had used WeChat to access and read health information (Xingting Zhang et al. 2017). It is apparent that WeChat has emerged as a crucial platform for searching, consuming, and sharing health information.

Despite the significant advantages of social media, many challenges remain regarding user engagement in health information sharing. It has been shown that social media users’ behavior tends to be focused on obtaining health information, and individuals’ intention to share health information is not strong (Zhou 2020). This imbalance can hinder the dissemination of valuable health information and the growth of online health communities. Many people expect a better life and have a strong need for healthcare, but their health literacy still needs to be improved (Wang et al. 2020). Sharing and dissemination of health information improves people’s health literacy which plays a public health a crucial role in public health (Chen et al. 2019; Junaidi et al. 2020; Wu and Kuang 2021). Given the increasingly important role of social media in the dissemination of health information (Afful-Dadzie et al. 2023), a deeper understanding of the drivers of health information sharing behaviors is paramount to increasing public engagement and optimizing health intervention strategies.

Available research has focused on three types of health information sharing: personal health information disclosure, health knowledge sharing, and general health information dissemination. For example, patients share their treatment experiences with their peers through online health communities (Zhang and Liu 2021), health professionals may share clinical experiences, disease prevention, and other health knowledge (Liu et al. 2020), and general users may share health information with their family and friends through social media (Hong et al. 2021; Zhang and Cozma 2022). This study focuses on the dissemination of general health information, which is the sharing of health information initially posted by others. This is because the dissemination of general health information has a critical role in promoting public health awareness and education and deserves more attention (Chung 2017; Le et al. 2022). When health information is widely and effectively disseminated, it can reach a broader audience, including those who may not actively seek specialized health knowledge or information. For health information providers, sharing behavior improves their health information to be seen by more users and increases exposure visibility (Shi et al. 2018). For users, they benefit from the act of sharing as it may enable them to accumulate their own healthcare knowledge base (Zhao et al. 2020).

It is worth noting that although existing research has used a singular theory to explain information sharing behaviors, such as the Uses and Gratification Theory (Wang and Chen 2022; Malik et al. 2023), the Social Support Theory (SST) (Li et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Rui 2022), the Theory of Reasoned Action (TRA)/ the Theory of Planned Behavior (TPB) (Karnowski et al. 2018; Chen 2020; Al-Husseini 2021), or the Social Capital Theory (SCT) (Lin et al. 2019; Hong et al. 2021; Wu and Kuang 2021). A comprehensive theoretical perspective on the factors that influence why and how users share health information on social media platforms has not been developed. TRA and TPB explored how users’ subjective norms and personal attitudes influence users’ intentions to share health information (Malik et al. 2023). Social support theory proposes that emotional and informational support from peers, friends, or family members encourages individuals to engage in health-related behaviors (Liu et al. 2019). And the social capital formed by users because of collaboration, communication, and interaction enhances networking, trust, and shared value, which allows them to share health information with others (Hong et al. 2021). These theories usually focus on a specific aspect and have not been able to fully capture the complexity of health information sharing behaviors (Chen 2020; Rui 2022). As a result, two research questions remain regarding these theories for health information sharing behavioral interactions:(1) What is the relationship between the help (social support) and resources (social capital) users receive from their social networks and their subjective norms and attitudes toward health information sharing? (2) How do users’ social support, social capital, and subjective norms and attitudes influence their health information sharing behavior?

To bridge this gap, this study integrates the TRA, SST, and SCT to provide a comprehensive framework for understanding the multiple motivators of health information sharing behaviors on social media.

Theoretical foundation and hypotheses

Theory of reasoned action

The TRA is a theoretical model that was first proposed by Fishbein and Ajzen (1975) to explain human behavior. The model suggested that people’s behavior is determined by their intentions, which are in turn influenced by their attitudes towards the behavior, as well as the subjective norms surrounding the behavior. The TRA model has been used to explain a wide range of behaviors, including health-related behaviors (Lewis et al. 2021), environmental behaviors (Prakash and Pathak 2017), and e-commerce (Copeland and Zhao 2020). The model has exhibited extensive applicability across various contexts and has demonstrated utility as a tool for comprehending and predicting behavior. (Ajzen 1991).

TRA models have been used to study health information intentions and behaviors, especially in the context of the Internet/mobile Internet (Chang and Huang 2020). However, to the best of our knowledge, there is very limited research examining the factors that contribute to health information sharing on social media. Other information sharing behaviors, such as the exchange of news, educational content, or expertise (e.g., Arpaci and Baloğlu 2016; Chedid et al. 2020; Chandran and Alammari 2021), While these messages have educational value, they usually lack the interactivity and communication dynamics for specific social settings or target groups. The context and purpose of health information sharing is distinct from other information (Southwell 2013), although health information may contain elements of general knowledge, its relevance is usually more direct and personal, with applications to everyday decision-making and health behaviors (Dadaczynski et al. 2021). Considering all the above, our study proposes that TRA model can be used to explore the health information sharing behavior of social media users.

Subjective norms

Subjective norms refer to an individual’s perceptions of the social pressure to engage in a specific behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980). According to TRA model, subjective norms are formed through the opinions and beliefs of others in an individual’s social network, as well as the influence of cultural and social norms surrounding the behavior. Individuals who perceive stronger subjective norms for a particular behavior tend to exhibit a greater intention to engage in that behavior (La Barbera and Ajzen 2020). In this study, subjective norms refer to the social pressures or social expectations that individuals perceive when sharing health information on social media. Prior studies have shown that subjective norms can significantly predict news sharing intentions (Kim et al. 2020; Lin and Wang 2020). And subjective norms are an important factor influencing social media users’ sharing of environmental risk information (Yang and Zhuang 2020) and health risk information (Malik et al. 2023). Thus, we proposed the following hypothesis:

H1: Subjective norms positively influence on user’s health information sharing intentions.

Attitude

Based on TRA model, attitude is another key factor that influences an individual’s intention to engage in a behavior which refers to the individual’s positive or negative evaluation of a specific behavior (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980). In this study, attitude refers to an individual’s overall evaluation and perception of the behavior of sharing health information on social media. Specifically, attitudes reflect users’ perceptions of whether the act of sharing health information is beneficial, interesting, or important, as well as the satisfaction they feel when engaging in such sharing (H.-C. Lin et al. 2018). Previous studies have shown that attitudes are effective predictors of behavioral intentions (Bae and Chang 2021; Kabir and Islam 2021). In a similar fashion, attitudes play an important role in influencing individuals’ information sharing intentions as well. Specifically, Kim et al. (2020) found that people’s positive attitudes had a positive influence on their intention to share information. This result was supported in a study of WeChat users’ intention to share health information (X. Wu and Kuang 2021). Therefore, we proposed that:

H2: Attitudes positively influence on user’s health information sharing intentions.

Social capital

The TRA model provides a solid foundation for understanding how personal attitudes and subjective norms influence users’ intentions to share health information on social media. However, TRA focuses primarily on individual-level determinants (Ajzen and Fishbein 1980), and social capital theory provides a complementary perspective by emphasizing the role of social interaction, trust, and shared vision in facilitating information sharing.

From a sociological perspective, social capital is a form of capital that is the sum of resources or capabilities mobilized through social networks for instrumental or affective purposes. Nahapiet and Ghoshal’s (1998) defines social capital as “the sum of actual and potential resources embedded in, acquired through, and derived from the network of relationships held by an individual or social unit” (p.243). Following them, social capital can be divided into structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions, which influence the creation and exchange of intellectual capital. The interactive nature of social media allows users to no longer participate in the communication process only as passive recipients of information, but to actively share the information they acquire (Nov et al. 2010). The social network space constructed by social media constitutes a good environment for users to create and share information.

Structural dimension – Social interaction

Prior studies identified social interaction, trust, and shared vision as the key constructs representing the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital (Junaidi et al. 2020; Al-Husseini 2021; Alajmi and Alasousi 2023). The structural dimension of social capital refers to the objective forms of connections between people or units, and the degree to which people in an organization are connected to each other (Bolino et al. 2002). It is usually expressed through social network ties between network members, and the more social interaction the stronger is the structural dimension of social capital (Chiu et al. 2006). In social media, social interactions are crucial for establishing connections (Prasetio 2014), and such connections influence users’ information processes and subsequent behavioral intentions (Shao and Pan 2019). Social interactions have been studied as a key contributor for information sharing (Li et al. 2022; Muliadi et al. 2022). Thus, a frequent social interaction helps users to get to know each other better and increases the probability that they share health information.

Studies have investigated users’ attitudes toward using social media and information sharing (Noh 2021; Bi and Cao 2023). When social interactions are present and friendly, members tend to share their knowledge and information (Zhi et al. 2023). Similarly, Al-Husseini (2021) argued that social interactions allow individuals to share ideas and thoughts easily and they have stronger attitudes towards performing such behaviors. Additionally, subjective norms reflect an individual’s perception of social pressure to perform a behavior (Aschwanden et al. 2021), and these pressures can significantly contribute to the prediction of intentions to engage in health-related behaviors (Shamlou et al. 2022). WeChat users with more social interactions feel more pressure to share information, while users need to follow appropriate subjective norms when communicating and interacting (Hong et al. 2021). Thus, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H3a: Social interaction positively influences subjective norms.

H3b: Social interaction positively influences attitude.

H3c: Social interaction positively influences user’s health information sharing intentions.

Cognitive dimension -Shared vision

The cognitive dimension refers to those resources providing shared representations, interpretations, and systems of meaning among parties (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). The key factors for this dimension are shared language and shared vision. Tsai and Ghoshal (1998) have argued that social capital is developed through a shared vision that reflects the collective goals and aspirations of an organization’s members. Members with a shared vision reflect the shared values, beliefs, and expectations of both parties involved in sharing information, and are more likely to become partners in sharing or exchanging information (Chiu et al. 2006). In this study, shared vision refers to the collective understanding, common goals, and shared aspirations of members of a user’s social network to share health information. The existence of a shared vision promotes mutual understanding and exchange of ideas, and users tend to contribute their own information or resources to help fulfill shared visions (Zhou 2020). Research has shown that shared values and visions for engaging in collaborative behaviors strongly influence individual’ sharing behaviors (Moser and Deichmann 2021; Noh 2021; Li et al. 2022)

Meanwhile, it has been suggested that shared vision can help promote similar perceptions among individuals and improve the efficiency of communication with others, thus increasing their attitudes toward sharing information about academic issues (Al-Husseini 2021). However, Hong et al. (2021) stated that shared vision positively influenced subjective norms but had no significant effect on attitudes. More evidence is needed to support the effect of shared vision on subjective norms and attitudes. Based on these, we believe that the shared vision of WeChat friends and group members to pursue physical and mental health can promote the perception of the significance of health information sharing, which in turn influences users’ subjective norms and attitudes. Ultimately, this can promote their health information sharing behaviors. Thus, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H4a: Shared vision positively influences subjective norms.

H4b: Shared vision positively influences attitude.

H4c: Shared vision positively influences user’s health information sharing intentions.

Relational dimension -Trust

The relational dimension of social capital focuses on special interpersonal relationships that enable them to achieve social motivations such as socialization, recognition and prestige, and influence their behavior (Nahapiet and Ghoshal 1998). Trust is related to people’s beliefs about others, including honesty, consistency of behavior, and keeping promises, and plays a crucial role in the online environment (Zafar et al. 2020). Trust in this study refers to an individual’s confidence and belief in the reliability, integrity, and trustworthiness of others in their social network when sharing health information. Existing studies have demonstrated that trust is an important contributor to knowledge and information sharing (Kumar et al. 2021; Wu and Kuang 2021; Bi and Cao 2023). Similarly, Zhou (2020) suggested that trust implies users’ recognition of health information provided by other users, which directly influences their behavior.

In the context of social media, trust influences subjective norms through an individual’s perception of social pressure to engage in behavior (Hosen et al. 2023). When users develop strong trust and approval of others and the platform, they are more likely to endorse and comply with subjective norms (Hong et al. 2021). Regarding the relationship between trust and attitudes, many scholars have examined the importance of trust as a determinant of individuals’ attitudes or intentions (Lin and Wang 2020; Gvili and Levy 2021; Zhi et al. 2023). Therefore, we proposed the hypotheses that:

H5a: Trust positively influences subjective norms.

H5b: Trust positively influences attitude.

H5c: Trust positively influences user’s health information sharing intentions.

Social support

Shumaker and Brownell (1984) defined social support as “an exchange of resources between at least two individuals perceived by the provider or the recipient to be intended to enhance the wellbeing of the recipient” (p. 13). Online social support is usually invisible and includes both informational and emotional support (Madjar 2008). From a social support perspective, health information sharing is an act of distributing information resources within an individual’s social network (Liu et al. 2019). Social support provides both informational assistance and mental comfort.

Social media provides a wealth of health information that can be valuable to people who wish to learn more about health issues. Health information sharing behaviors contain more social elements than other health information behaviors (e.g., health information seeking or avoidance behaviors) (Liu et al. 2019; Wu and Kuang, 2021). Users receive information support and emotional support through interactions with their friends, and strong social support helps promote their intention to share health information (Wu and Kuang 2021). Studies have found that individuals’ perceived emotional and informational support has a positive impact on health information sharing behavior (Li et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019; Rui, 2022).

Specifically, emotional support reflects the emotional comfort from other users such as attention, concern, encouragement, and trust (Hajli 2014). Emotional support can be expressed in many ways, including providing listening, expressing understanding, offering assurance, and showing concern. The intimate relationships developed by users in WeChat form trust and identity with each other, and this trust can be seen as a kind of emotional support (Zhou 2020). Thus, the relational dimensions of emotional support and the previously discussed social capital can share the hypothesis.

Informational support

Informational support is a type of social support that involves the provision of advice, guidance, and information to individuals (Barrera 1986). It is especially crucial in situations where individuals lack knowledge or expertise or face complex or uncertain issues. Zhou (2020) stated that the positive experience of using social media when friends provide valuable information or timely help makes users more willing to engage in social interactions, and support providers will gain recognition and satisfaction from the interaction. In addition, a high level of informational support can help users integrate quickly into their group (Hajli 2014), and be influenced by subjective norms to voluntarily share health information. Therefore, we proposed the following hypotheses:

H6a: Informational support positively influences subjective norms.

H6b: Informational support positively influences attitude.

H6c: Informational support positively influences user’s health information sharing intentions.

Method

Measures

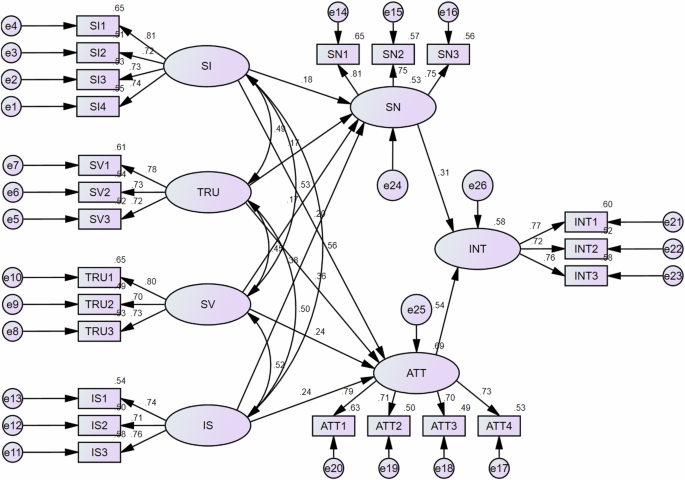

Combining hypotheses about the relationship between Social Capital, Social Support, and TRA model, a research model was developed for this study, as shown in Fig. 1. A two-part questionnaire was used in this study to test these hypotheses. The first part comprised of demographic information including gender, age, education level, monthly income, and the amount of time spent daily using the Internet and WeChat. The second part of the questionnaire consisted of a measure of the key constructs being studied. To measure each construct, we adapted items from previous studies.

Specifically, the structural, relational, and cognitive dimensions of social capital were measured using 10 items adapted from Lin and Lu (2011). Information support was measured using three items adapted from Zhou (2020). Subjective norms and attitudes were measured using seven items adapted from Chen et al. (2018). We adapted the statement of the items to match the context of this study. Finally, health information sharing intentions were measured using three items from Hong et al. (2021). All items were related to the current study and have been empirically validated with adequate reliability and validity. A 7-point Likert scale ranging strongly disagree (1) to neutral (4) to strongly agree (7) was implemented across all subscales for consistency in response. The full version of the instrument is presented in Appendix A. Table 1 provides a descriptive statistic (mean and standard deviation) for these items.

Sample and data collection

Before recruiting the participants, we conducted a priori power analysis using G*Power software and found that a minimum of 123 participants were required to identify medium effects (f2 = 0.15), with a significance level of 0.05 and a power of 0.9 (Faul et al. 2009). Our final sample size exceeded this requirement, ensuring sufficient statistical power.

The data collection process is completed using Credamo (https://www.credamo.com), a professional data platform in China. With a sample database of over 3 million participants, Credamo provides large-scale data collection services and has been recognized by top international journals in the fields of psychology, management, sociology and medicine (Jin et al. 2020). It is also recognized by national surveys and official reports as a reliable data collection tool (Pian et al. 2024). This platform provides access to a large and diverse participant pool, representing various demographics and regions across mainland China.

In addition to utilizing Credamo, a snowball sampling method was employed. The survey was distributed via the authors’ network of WeChat friends, who were then encouraged to share it further within their networks. This mixed sampling method allows for broad coverage and increases the likelihood of a representative sample. Similar approaches have been used in previous studies (Li 2020; Jiao et al. 2024). To minimize potential sampling bias between the two methods (Bornstein et al. 2013), we conducted a t-test to compare demographic variables between participants recruited via Credamo and those obtained through snowball sampling. The results showed no statistically significant differences between the two groups (p > 0.05), indicating that the samples from both methods are comparable, reducing the likelihood of systematic bias.

Since the instrument was originally developed in English and the research context was in China, we used back translation methods to translate it into Chinese. We invited a bilingual expert to first translate the English version of the instrument into Chinese. Then, another bilingual expert translated the Chinese version into English. We compared the two English versions to check for inconsistencies and resolved them through discussion. After completing the development of the instrument, 30 participants who regularly use WeChat were invited to complete a pilot study. Based on their comments, some items were modified to improve the clarity and comprehensibility of the questionnaire.

The data collection procedure was conducted from November 1 to December 31, 2023. Out of the initial 374 received questionnaires, 21 were found to be invalid or incomplete and were therefore discarded, leaving a total of 353 valid questionnaires for analysis. Demographic statistics of the respondents are shown in Table 2. Approximately 55% of the respondents were male and 45% were female. More than half of the respondents (62%) were between the ages of 18 and 30. As for education, the majority of respondents (69.1%) had a bachelor’s degree, 62.3% use the Internet for 2–6 h per day, and slightly over half of respondents (54.5%) use WeChat for 61–150 min per day.

Data analysis and results

To identify the causal relationships between structural variables and examine both the measurement items and the structural model, the structural equation modeling (SEM) was employed in this study. The two-step approach recommended by Anderson and Gerbing (1988) was used in this study. We measured the validity of the model, before the structural modeling to test the direct and indirect effects of the model.

Outer Model and Scale Validation

Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was used to evaluate the convergent validity of the model. Reliability is tested based on Cronbach’s alpha and composite reliability (CR), each of which should be no less than 0.70 to be statistically reliable (Collier 2020). Convergent validity can be evaluated by checking the average variance extracted (AVE), and the AVE value for each construct should be greater than 0.5 (Gefen et al. 2000). As shown in Table 3, all factor loadings, CR and AVE are acceptable, which indicated good reliabilities and a good convergent validity of the scales.

Discriminant validity tests the degree of discrimination between the test variables and the different construct criteria. As shown in Table 4, the square root of AVE is greater than the correlation coefficient with the other structures in the model, which means that all structures have adequate discriminant validity (Fornell and Larcker 1981). The results of the fit of the structural model to the data obtained with the maximum likelihood estimation showed that the model had a good fit, as shown in Table 5. Most other measures of fit, including χ2 per degree of freedom, were in the acceptable range and above the minimum recommended values.

Inner Model and Hypotheses Test

Following confirmation of the external model’s good measurement properties, we proceeded to analyze the internal model to evaluate its explanatory power, path coefficients, and tests of hypotheses. As shown in Fig. 2, the study model had an overall R2 of 59.9% for intention to share health information, R2 of 65.6% for subjective norms, and R2 of 51.3% for attitudes. This indicates that the model was effective in elucidating the intention to share health information through WeChat. This explanatory power attests to the predictive validity of our model, as outlined by Kline (2015).

Our proposed hypotheses were mostly supported, as shown in Table 6. Specifically, the results revealed that the paths of health information sharing intention through subjective norms and attitudes were significant, supporting hypotheses H1 and H2. Social interaction was significant for both the hypothesized paths of subjective norms, attitudes, and health information sharing intention, thus supporting hypotheses H3a, H3b and H3c. Shared vision was significant for both the paths of subjective norms, attitudes and health information sharing intention, thus hypotheses H4a, H4b and H4c were supported. Trust was significant for both paths of subjective norms and attitudes, supporting hypotheses H5a and H5b. Paths of trust to health information sharing intentions are not significant, so H5c was not supported. The hypothesized paths of informational support on subjective norms and attitudes were both significant at the p < 0.001 level, but not significant on health information-sharing intentions. Thus, supporting hypotheses H6a and H6b, and hypothesis H6c was not supported.

Discussion

This study integrated Social Capital Theory, Social Support Theory and Theory of Rational Action model to analyze WeChat users’ health information sharing intention. The results showed that users’ subjective norms, attitudes, and social capital, especially social interactions with others and shared visions, had a significant effect on health information sharing intentions, whereas trust and informational support had no significant effect on sharing intentions.

From a theoretical perspective, previous studies have tended to examine these factors in isolation, which limits the understanding of how they interact to influence health behaviors in complex digital environments (Liu et al. 2019; XZ and Liu 2021; Wang et al. 2022). Our study demonstrates the necessity of combining these models to capture the multifaceted nature of health communication. While TRA explains how subjective norms and attitudes predict sharing intentions, it does not explain the impact of the social networks and support structures that underpin these cognitive processes. By incorporating Social Capital and Social Support Theory, we provide a more integrated framework that better reflects real-world health communication scenarios.

Specifically, the study indicated that subjective norms and attitudes had a significant positive effect on health information sharing intentions, which is in line with previous research (Chen 2020; Wu and Kuang 2021). As Kim et al. (2020) mentioned, WeChat users may have a positive attitude toward the information and be willing to share it with others if they perceive the information as meaningful to their own or others’ health as well as perceive social pressure from others to share the information. Second, all three different dimensions of social capital have a positive effect on subjective norms and attitudes. This suggests that the more frequently users interact with others, and the stronger the shared vision and trust between them, the more positive attitudes and subjective norms are formed (Hong et al. 2021).

The results show that trust significantly influences attitudes and subjective norms, but not on health information sharing intentions, which is not consistent with previous research (Smaliukienė et al. 2017; Kumar et al. 2021). Our findings provide evidence that different from general information sharing, the drivers of health information sharing are more nuanced and context specific. Emotional support provided by friends in social networks as a factor of social support does not necessarily promote the sharing of health information among users due to differences in group, age, and individual status (Wu et al. 2022). These findings expand the existing theoretical understanding of the role of trust. In particular, this study reveals that trust may weaken its direct effect on shared intentions in complex social networks due to diverse social relationships and differences in emotional support, and that WeChat users, who have complex and diverse relationships in their social networks, may impede the transmission of trust by segmenting or splitting individual trust relationships.

As far as information support is concerned, our study provides new insights into how different aspects of social support influence health information sharing. The findings suggest that information support positively affects subjective norms and attitudes, but does not directly affect sharing intentions, which contradicts some earlier research (Li et al. 2018; Rui 2022). Based on Ta et al. (2020), information support may be more oriented towards functional support, mainly providing information and advice, with a weaker connection to the users’ emotional experience and social identity. Health information sharing, on the other hand, is more of a social behavior that needs to be driven by the subjective will of the user. This implies that while informational support can shape perceptions and attitudes, it may lack the affective connection needed to drive actual sharing behaviors. This challenges the traditional understanding of social support in health communication and suggests that different types of support may play different roles in influencing health behaviors. It emphasizes the importance of emotional and relational dimensions in promoting sharing and suggests that future research should consider how different forms of support interact to influence health communication.

In addition, the findings of this study have important practical implications for the design of interventions aimed at promoting health information sharing among WeChat users. First, the study highlights the importance of attitudes and subjective norms. Thus, by providing reliable and accurate health information to WeChat users, promoting transparency and accountability in health communication, and addressing concerns about privacy and confidentiality. Furthermore, considering social support is not sufficient to influence users’ intention to share health information, health information providers (e.g., WeChat account publishers, group members, etc.) can be guided to focus on providing users with health information that meets their needs and preferences and helps to promote the dissemination of health information. By taking these practical implications into account, interventions aimed at promoting health information-sharing behaviors among WeChat users can be more effective.

While this study provides important insights into the health information-sharing behaviors of Chinese social media users, there are some limitations that warrant attention in future studies First, the cross-sectional design limited the ability to establish causal relationships between social capital, social support, the TRA model, and health information sharing behavior. Future research could use longitudinal studies to examine pathways of causality and possible changes in health information-sharing intentions over time. Second, the survey respondents were WeChat users in mainland China. As one of the most popular social media in the world, users in different regions may have different health information-sharing performances due to ethnic, and cultural differences, and future research could explore user behavior from different cultural backgrounds.

Conclusion

By applying Social Capital Theory, Social Support Theory and Theory of Reasoned Action to explore the factors influencing WeChat users’ health information sharing intention, this study identified that social capital factors play a key role in facilitating the communication of health information. Strengthening social interactions, shared visions, and trusting relationships among users can help create a community atmosphere that supports health information sharing and enhances users’ sense of identity and motivation to share. In contrast, social support, while also influencing users’ personal norms and attitudes, may be segmented or diluted in complex social networks, thus failing to promote health information sharing. The results contribute to health communication research by emphasizing the importance of integrating multiple theoretical perspectives to better understand the complex factors that drive health information behavior in social media environments.

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

-

Afful-Dadzie E, Afful-Dadzie A, Egala SB (2023) Social media in health communication: A literature review of information quality. HIM J. 52(1):3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358321992683

-

Ajzen I (1991) The theory of planned behavior. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process. 50(2):179–211. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(91)90020-T. Theories of cognitive self-regulation

-

Ajzen I, Fishbein M (1980) Understanding Attitudes and Predicting Social Behavior. 1st edition. Pearson, Englewood Cliffs, NJ

-

Alajmi BM, Alasousi SO (2023) Cultivating knowledge sharing among academics: the role of social media and the impact of social capital. Journal of electronic resources librarianship. World

-

Al-Husseini SJ (2021) Social capital and individual motivations for information sharing: A theory of reasoned action perspective. Journal of Information Science.:01655515211060532. https://doi.org/10.1177/01655515211060532

-

Anderson JC, Gerbing DW (1988) Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychol. Bull. 103:411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

-

Arpaci I, Baloğlu M (2016) The impact of cultural collectivism on knowledge sharing among information technology majoring undergraduates. Comput. Hum. Behav. 56:65–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.031

-

Aschwanden D, Strickhouser JE, Sesker AA et al. (2021) Preventive Behaviors During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Associations With Perceived Behavioral Control, Attitudes, and Subjective Norm. Frontiers in public health. 9

-

Bae SY, Chang P-J (2021) The effect of coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) risk perception on behavioural intention towards ‘untact’ tourism in South Korea during the first wave of the pandemic (March 2020). Curr. issues Tour. 24(7):1017–1035. https://doi.org/10.1080/13683500.2020.1798895

-

Barrera M (1986) Distinctions between social support concepts, measures, and models. Am. J. Commun. Psychol. 14(4):413–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF00922627

-

Bi X, Cao X (2023) Understanding knowledge sharing in online health communities: A social cognitive theory perspective. Inf. Dev. 39(3):539–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669221130552

-

Bolino MC, Turnley WH, Bloodgood JM (2002) Citizenship behavior and the creation of social capital in organizations. Acad. Manag. Rev. 27(4):505–522. https://doi.org/10.2307/4134400

-

Bornstein MH, Jager J, Putnick DL (2013) Sampling in developmental science: Situations, shortcomings, solutions, and standards. Dev. Rev. 33(4):357–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2013.08.003

-

Chandran D, Alammari AM (2021) Influence of culture on knowledge sharing attitude among academic staff in eLearning Virtual Communities in Saudi Arabia. Inf. Syst. Front 23(6):1563–1572. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10796-020-10048-x

-

Chang C-C, Huang M-H (2020) Antecedents predicting health information seeking: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 54:102115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2020.102115

-

Chedid M, Caldeira A, Alvelos H et al. (2020) Knowledge-sharing and collaborative behaviour: An empirical study on a Portuguese higher education institution. J. Inf. Sci. 46(5):630–647. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165551519860464

-

Chen J, Wang Y (2021) Social media use for health purposes: systematic review. J. Med Internet Res 23(5):e17917. https://doi.org/10.2196/17917

-

Chen L, Baird A, Straub D (2019) Fostering participant health knowledge and attitudes: an econometric study of a chronic disease-focused online health community. J. Manag. Inf. Syst. 36(1):194–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/07421222.2018.1550547

-

Chen Y (2020) An investigation of the influencing factors of Chinese WeChat users’ environmental information-sharing behavior based on an integrated model of UGT, NAM, and TPB. Sustainability 12(7):2710. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12072710

-

Chen Y, Liang C, Cai D (2018) Understanding WeChat users’ behavior of sharing social crisis information. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 34(4):356–366. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2018.1427826

-

Chiu C-M, Hsu M-H, Wang ETG (2006) Understanding knowledge sharing in virtual communities: An integration of social capital and social cognitive theories. Decis. Support Syst. 42(3):1872–1888. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dss.2006.04.001

-

Chung JE (2017) Retweeting in health promotion: Analysis of tweets about Breast Cancer Awareness Month. Comput. Hum. Behav. 74:112–119. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.04.025

-

Collier J (2020) Applied Structural Equation Modeling using AMOS: Basic to Advanced Techniques. Routledge, New York. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003018414

-

Copeland LR, Zhao L (2020) Instagram and theory of reasoned action: US consumers influence of peers online and purchase intention. Int. J. Fash. Des., Technol. Educ. 13(3):265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/17543266.2020.1783374

-

Dadaczynski K, Okan O, Messer M et al. (2021) Digital health literacy and web-based information-seeking behaviors of university students in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic: cross-sectional survey study. J. Med. internet Res. 23(1):e24097. https://doi.org/10.2196/24097

-

Faul F, Erdfelder E, Buchner A et al. (2009) Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 41(4):1149–1160. https://doi.org/10.3758/BRM.41.4.1149

-

Fishbein M, Ajzen I (1975) Belief, Attitude, Intention and Behavior: An Introduction to Theory and Research. Addison-Wesley, Reading, Mass

-

Fornell C, Larcker DF (1981) Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. J. Mark. Res. 18(1):39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104

-

Gefen D, Straub D, Boudreau M (2000) Structural equation modeling and regression: guidelines for research practice. Communications of the Association for Information Systems. 4. https://doi.org/10.17705/1CAIS.00407

-

Gvili Y, Levy S (2021) Consumer engagement in sharing brand-related information on social commerce: the roles of culture and experience. J. Mark. Commun. 27(1):53–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/13527266.2019.1633552

-

Hajli MN (2014) The role of social support on relationship quality and social commerce. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 87:17–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2014.05.012

-

Hong Y, Wan M, Li Z (2021) Understanding the health information sharing behavior of social media users: an empirical study on WeChat. J. Organ. End. Use Comput. 33(5):180–203. https://doi.org/10.4018/JOEUC.20210901.oa9

-

Hosen M, Ogbeibu S, Lim WM et al. (2023) Knowledge sharing behavior among academics: Insights from theory of planned behavior, perceived trust and organizational climate. J. Knowl. Manag. 27(6):1740–1764. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-02-2022-0140

-

Jiao W, Schulz PJ, Chang A (2024) Addressing the role of eHealth literacy in shaping popular attitudes towards post-COVID-19 vaccination among Chinese adults. Humanit Soc. Sci. Commun. 11(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03656-4

-

Jin X, Li J, Song W et al. (2020) The Impact of COVID-19 and Public Health Emergencies on Consumer Purchase of Scarce Products in China. Front. Public Health. 8. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.617166

-

Junaidi J, Chin W, Ortiz J (2020) Antecedents of information seeking and sharing on social networking sites: an empirical study of Facebook users. Int. J. Commun. 14:5705–5728

-

Kabir MR, Islam S (2021) Behavioural intention to purchase organic food: Bangladeshi consumers’ perspective. Br. food J. 124(3):754–774. https://doi.org/10.1108/BFJ-05-2021-0472

-

Karnowski V, Leonhard L, Kümpel AS (2018) Why users share the news: a theory of reasoned action-based study on the antecedents of news-sharing behavior. Commun. Res. Rep. 35(2):91–100. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824096.2017.1379984

-

Kim J, Namkoong K, Chen J (2020) Predictors of online news-sharing intention in the U.S and South Korea: An application of the theory of reasoned action. Commun. Stud. 71(2):315–331. https://doi.org/10.1080/10510974.2020.1726427

-

Kline RB (2015) Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling, Fourth Edition. Guilford Publications

-

Kumar TBJ, Goh S-K, Balaji MS (2021) Sharing travel related experiences on social media – Integrating social capital and face orientation. J. Vacat. Mark. 27(2):168–186. https://doi.org/10.1177/1356766720975047

-

La Barbera F, Ajzen I (2020) Control interactions in the theory of planned behavior: rethinking the role of subjective norm. Eur. J. Psychol. 16(3):401–417. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v16i3.2056

-

Le LH, Hoang PA, Pham HC (2022) Sharing health information across online platforms: A systematic review. Health Commun. 0(0):1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2021.2019920

-

Lewis J, Crawford S, Sullivan-Boylai S et al. (2021) A clinical trial of a video intervention targeting opioid disposal after general surgery: a feasibility study. J. Surg. Res. 262:6–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jss.2020.12.010

-

Li F (2020) Understanding Chinese tourists’ motivations of sharing travel photos in WeChat. Tour. Manag. Perspect. 33:100584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tmp.2019.100584

-

Li Y, Wang X, Lin X et al. (2018) Seeking and sharing health information on social media: A net valence model and cross-cultural comparison. Technol. Forecast. Soc. Change 126:28–40. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2016.07.021

-

Li Z, Lin Z, Nie J (2022) How personality and social capital affect knowledge sharing intention in online health support groups?: A Person-Situation Perspective. Int. J. Hum.–Comput. Interact. World

-

Lin H-C, Chen YJ, Chen C-C et al. (2018) Expectations of social networking site users who share and acquire health-related information. Computers Electr. Eng. 69:808–814. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compeleceng.2018.02.014

-

Lin KY, Lu HP (2011) Intention to continue using Facebook fan pages from the perspective of social capital theory. Cyberpsychol, Behav. Soc. Netw. 14:565–570. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0472

-

Lin X, Sarker S, Featherman M (2019) Users’ psychological perceptions of information sharing in the context of social media: a comprehensive model. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 23(4):453–491. https://doi.org/10.1080/10864415.2019.1655210

-

Lin X, Wang X (2020) Examining gender differences in people’s information-sharing decisions on social networking sites. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 50:45–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.05.004

-

Liu M, Yang Y, Sun Y (2019) Exploring health information sharing behavior among Chinese older adults: a social support perspective. Health Commun. 34(14):1824–1832. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1536950

-

Liu QB, Liu X, Guo X (2020) The effects of participating in a physician-driven online health community in managing chronic disease: evidence from two natural experiments. MISQ 44(1):391–419. https://doi.org/10.25300/MISQ/2020/15102

-

Madjar N (2008) Emotional and informational support from different sources and employee creativity. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 81(1):83–100. https://doi.org/10.1348/096317907X202464

-

Malik A, Mahmood K, Islam T (2023) Understanding the Facebook users’ behavior towards COVID-19 information sharing by integrating the theory of planned behavior and gratifications. Inf. Dev. 39(4):750–763. https://doi.org/10.1177/02666669211049383

-

Moser C, Deichmann D (2021) Knowledge sharing in two cultures: the moderating effect of national culture on perceived knowledge quality in online communities. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 30(6):623–641. https://doi.org/10.1080/0960085X.2020.1817802

-

Muliadi M, Muhammadiah M, Amin KF et al. (2022) The information sharing among students on social media: the role of social capital and trust. VINE J. Inf. Knowl. Manag. Syst. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print). https://doi.org/10.1108/VJIKMS-12-2021-0285

-

Nahapiet J, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital, intellectual capital, and the organizational advantage. Acad. Manag. Rev. 23(2):242–266. https://doi.org/10.2307/259373

-

Noh S (2021) Why do we share information? Explaining information sharing behavior through a new conceptual model between sharer to receiver within SNS. Asia Pac. J. Inf. Syst. 31(3):392–414. https://doi.org/10.14329/apjis.2021.31.3.392

-

Nov O, Naaman M, Ye C (2010) Analysis of participation in an online photo-sharing community: A multidimensional perspective. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 61(3):555–566. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.21278

-

Pian W, Zheng R, Potenza MN et al. (2024) Health information craving: Conceptualization, scale development and validation. Inf. Process. Manag. 61(4):103717. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2024.103717

-

Prakash G, Pathak P (2017) Intention to buy eco-friendly packaged products among young consumers of India: A study on developing nation. J. Clean. Prod. 141:385–393. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.09.116

-

Prasetio A (2014) Understanding Knowledge Sharing and Social Capital in Social Network Sites 3(3)

-

Rui JR (2022) Health Information Sharing via Social Network Sites (SNSs): Integrating Social Support and Socioemotional Selectivity Theory. Health Commun.:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2074779

-

Shamlou Z, Saberi MK, Amiri MR (2022) Application of theory of planned behavior in identifying factors affecting online health information seeking intention and behavior of women. Aslib J. Inf. Manag. 74(4):727–744. https://doi.org/10.1108/AJIM-07-2021-0209

-

Shao Z, Pan Z (2019) Building Guanxi network in the mobile social platform: A social capital perspective. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 44:109–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2018.10.002

-

Shi J, Poorisat T, Salmon CT (2018) The Use of Social Networking Sites (SNSs) in health communication campaigns: review and recommendations. Health Commun. 33(1):49–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2016.1242035

-

Shumaker SA, Brownell A (1984) Toward a theory of social support: closing conceptual gaps. J. Soc. issues 40(4):11–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1984.tb01105.x

-

Smaliukienė R, Bekešienė S, Chlivickas E et al. (2017) Explicating the role of trust in knowledge sharing: a structural equation model test. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 18(4):758–778. https://doi.org/10.3846/16111699.2017.1317019

-

Southwell BG (2013) Social Networks and Popular Understanding of Science and Health: Sharing Disparities. JHU Press

-

Ta V, Griffith C, Boatfield C et al. (2020) User experiences of social support from companion chatbots in everyday contexts: thematic analysis. J. Med. internet Res. 22(3):e16235. https://doi.org/10.2196/16235

-

Tsai W, Ghoshal S (1998) Social capital and value creation: the role of intrafirm networks. Acad. Manag. J. 41(4):464–476. https://doi.org/10.2307/257085

-

Wallace C, McCosker A, Farmer J et al. (2021) Spanning communication boundaries to address health inequalities: the role of community connectors and social media. J. Appl. Commun. Res. World

-

Wang W, Zhang Y, Lin B et al. (2020) The urban-rural disparity in the status and risk factors of health literacy: a cross-sectional survey in Central China. Int J. Environ. Res Public Health 17(11):3848. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17113848

-

Wang X, Zuo Z, Tong X et al. (2022) Talk more about yourself: a data-driven extended theory of reasoned action for online health communities. Inf. Technol. Manag. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10799-022-00376-6

-

Wang Y, Chen J (2022) What motivates information seeking and sharing during a public health crisis? A combined perspective from the uses and gratifications theory and the social- mediated crisis communication model. J. Int. crisis risk Commun. Res. 5(2):155–184

-

Wu S, Zhang J, Du L (2022) I Do Not Trust Health Information Shared by My Parents”: Credibility judgement of health (Mis)information on social media in China. Health Commun. 0(0):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2022.2159143

-

Wu X, Kuang W (2021) Exploring influence factors of WeChat Users’ health information sharing behavior: based on an integrated model of TPB, UGT and SCT. Int. J. Hum. –Comput. Interact. 37(13):1243–1255. https://doi.org/10.1080/10447318.2021.1876358

-

Yang JZ, Zhuang J (2020) Information seeking and information sharing related to hurricane Harvey. J. Mass Commun. Q. 97(4):1054–1079. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699019887675

-

Zafar AU, Qiu J, Shahzad M (2020) Do digital celebrities’ relationships and social climate matter? Impulse buying in f-commerce. Internet Res. 30(6):1731–1762. https://doi.org/10.1108/INTR-04-2019-0142

-

Zhang XA, Cozma R (2022) Risk sharing on Twitter: Social amplification and attenuation of risk in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Comput. Hum. Behav. 126:106983. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2021.106983

-

Zhang X, Liu S (2021) Understanding relationship commitment and continuous knowledge sharing in online health communities: a social exchange perspective. J. Knowl. Manag. 26(3):592–614. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-12-2020-0883

-

Zhang X, Wen D, Liang J et al. (2017) How the public uses social media wechat to obtain health information in China: A survey study. BMC Med. Inform. Decis. Making. 17. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12911-017-0470-0

-

Zhao H, Fu S, Chen X (2020) Promoting users’ intention to share online health articles on social media: The role of confirmation bias. Inf. Process. Manag. 57(6):102354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ipm.2020.102354

-

Zhi F, Zhang M, Zhang S et al. (2023) Can social capital and planned behaviour favour an increased willingness to share scientific data? Evidence from data originators. Electron. Libr. 41(4):456–473. https://doi.org/10.1108/EL-01-2023-0005

-

Zhou T (2020) Understanding users’ participation in online health communities: A social capital perspective. Inf. Dev. 36(3):403–413. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266666919864620

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Contributions

Conceptualization, C.J. and H.Q.; methodology, C.J. and H.Q.; formal analysis, C.J; writing—original draft preparation, C.J.; writing—review and editing, C.J. and H.Q.; supervision, H.Q.

Corresponding author

Ethics declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards stipulated in the Declaration of Helsinki and its subsequent amendments. Ethical clearance and approval were granted by the College of Literature and Journalism, Leshan Normal University, on Jun 14th, 2023.

Informed consent

Informed consent for this study was obtained via the Credamo platform before data collection began on 30/10/2023. Participants were provided with detailed information about the study and asked to give their consent by selecting the appropriate option in the online questionnaire. They were fully informed about the study’s nature and purpose, with assurance that the data would be used exclusively for academic purposes. Participant anonymity is guaranteed, as no personally identifiable information is collected or stored, and their responses would remain confidential. Additionally, participants were notified that there are no foreseeable risks involved in the study and that they could withdraw at any point without facing any consequences. At the end of the survey, each participant was compensated with CN ¥30 (approximately US $4) e-commerce vouchers.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

About this article

Cite this article

Jia, C., Qi, H. Users’ health information sharing behavior in social media: an integrated model.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun 11, 1647 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04188-7

-

Received:

-

Accepted:

-

Published:

-

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04188-7

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content