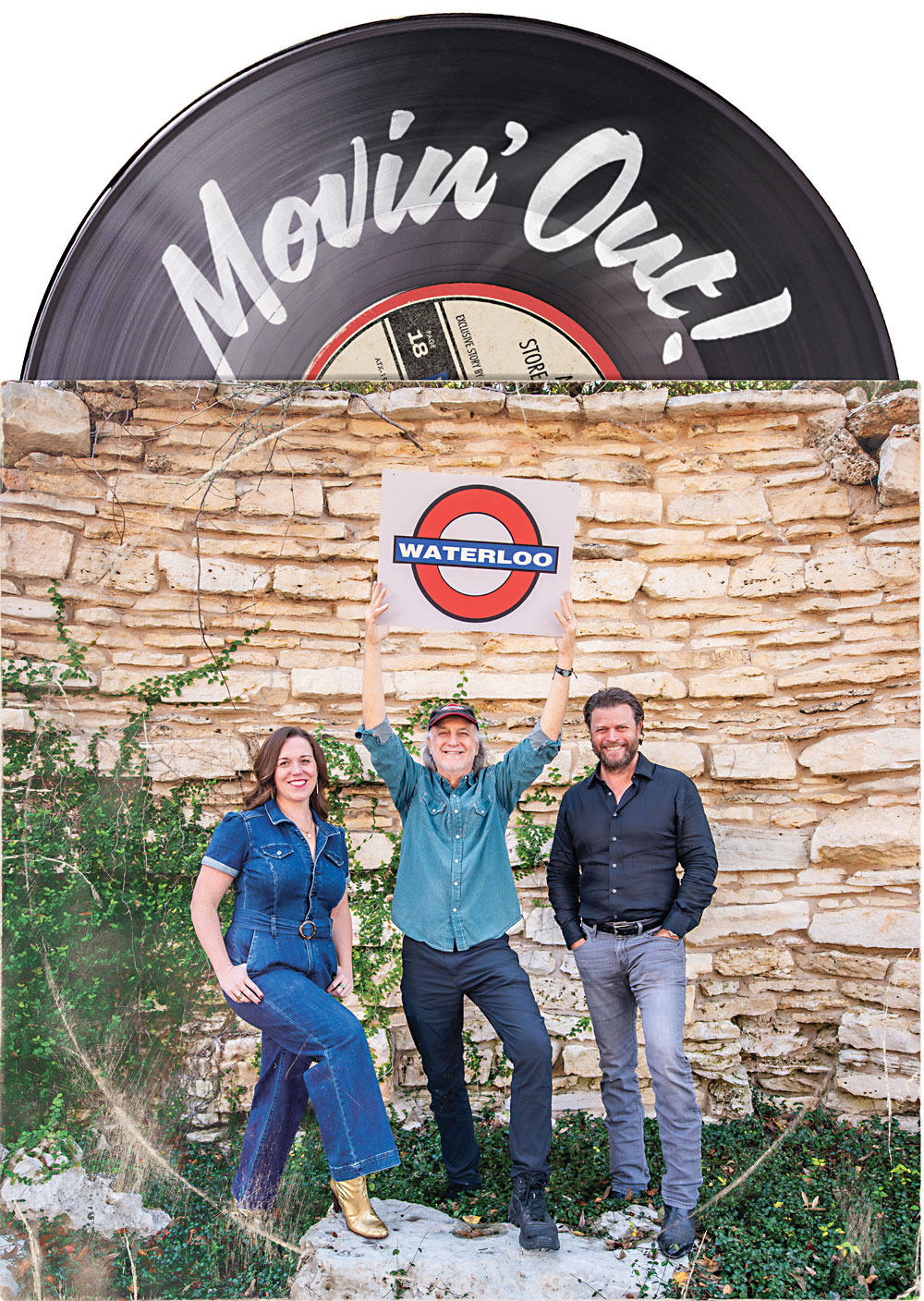

Waterloo Records’ new ownership team: (l-r) Caren Kelleher, John Kunz, and Trey Watson (Photo by David Brendan Hall / Design by Zeke Barbaro)

Toward the close of 2019, the northwest corner lot at Sixth and Lamar sold. Targeted for redevelopment, Waterloo Records’ literal foundation for three full decades suddenly entered turnaround. For owner John Kunz, the five-year odyssey that followed caps a lifetime of selling dreams to Austin and beyond.

“For what it’s worth,” he chuckles, “Endeavor’s been a really good landlord considering they bought the building to demo it. The property was sold to go as vertical as it could go.”

On Dec. 2, 2024, a bright and sunny Monday morning after Thanksgiving, the music retail pioneer stands in the entryway to the future home of Waterloo Records. His new partners, Caren Kelleher and Trey Watson, look around as light streams through the two-story front door. They estimate the ink on this new triumvirate at “a couple days” old.

At 1105 N. Lamar – five blocks up the boulevard from the current store – Kunz walks over to a thick window at the base of the inside front steps.

“Originally, it was a Louis Shanks Furniture showroom, then after the Shoal Creek flood of ’80, they moved to Anderson Lane,” he explains, touching the wall. “A former partner of mine and a leasing agent for where I am now purchased this building 20 years ago, and flood-proofed it to right here.”

Opening behind him like a Texas dance hall, the 9,650-square-foot building gains three thousand-plus on the current Waterloo. Winter light reveals a big, roomy ambience looking out through another set of corner windows on the world. By the time Kunz returns two weeks later, half the offices along the back corner will be removed in ongoing renovations.

The loading dock reveals a sizable lot outside, as well as diverse street parking barely existent at the current location. Patios will serve a second tenant at street level with Waterloo, while a second floor mirrors the first and remains empty. Kelleher dubs one deck the “soundgarden.”

Back inside, the three principals laugh and point – motion, wave, air-draw. Like proud new property owners on a reality series, they size up their future: excited, nervous, wondrous. They know that in this day-one boomtown of forever vanishing musical legacies, from the Armadillo World Headquarters to the Lost Well, tomorrow arrived today.

Relentless

Dec. 13 dawns needlessly doomy in the Lone Star seat – every shade of gray, black, and drizzle – which worsens throughout the day. Friday morning inside its current locale, Waterloo Records whistles and hums. Holidays or no, it always feels like Christmas in here.

Riding shotgun down to Waterloo 3.0, its torchbearer estimates the distance around 704 yards, then corrects himself to 709 in honor of the Uranium Savages. Kunz can’t find the new building code, so we follow the flow of workers and contractors sprucing up the entire property as they stream out the back. A single question greets him today.

“Well … no comment,” he laughs – we both laugh. “Had to say that. Had to say that.”

Waterloo’s dad takes a long, deep pause.

“I was always hoping and wishing I could find a way to pass the store on to a member or members of my crew,” he says in a near murmur. “Some of the ones I thought would be interested [weren’t], because they themselves are coming up on retirement age in the not-so-distant future. So then it fell to younger members.

“When we started, it was done on a shoestring [budget], but 42 years later, it’s a big bite for someone to take, and money and financing were not magically appearing. However, we had an angel investor that was down to purchase the company and let it live on doing what it’s doing.

“That was supposed to have closed March 31, 2020.”

COVID took down that deal, plus a final three-year lease with Endeavor Real Estate Group.

Going month-to-month with rent actually suited Waterloo Records’ second total location since bowing at 221 S. Lamar in 1982. Initially closed and running curbside service, the business made it through the pandemic by the grace of vinyl suddenly spinning and surging throughout social distancing. Meanwhile, team Kunz called in every commercial real estate sign that went up around town.

“For 42 years, I would’ve loved to have been able to buy my building,” he says. “I was a small minority partner in [600 Lamar]. At one time, I was offered to purchase it, but it wasn’t being sold to remain a single-story building and it wasn’t my intention to become a developer. I just wanted to have a record store that was on stable ground.”

A new location and 10-year lease solved only one-half of the issue, however. At 73, Kunz envisions a future in Downtown Austin beyond inventory management.

Or so he claims.

Returned to the current HQ, he retrieves a Bill Hicks CD after a car ride discussion on compact discs (“sales are up”). Recorded in 1991 at The Laff Stop in Austin, the local comic’s second live album bottles his kinetic, shooting star life. Before the question can be posed, Kunz snatches up a Hannibal Lokumbe reissue I uncover in the used vinyl section to, indeed, squirrel it away in his employee buy bin.

Appetite for Construction

At our first meet, Caren Kelleher wears a fur-lined suede coat, jeans, and a Guns N’ Roses T-shirt. Ninety minutes after Kunz absconds with the LP of his beloved Smithville trumpeter, she swings wide a nondescript front door in an industrial mall on Rutherford Lane, up to her knees in Valentine’s Day shipments. Gold Rush Vinyl’s scrap wax bouquets sell better than real roses.

Born and raised in Maryland to a hotelier and real estate agent, then Emory educated and crowned with a Harvard MBA, Kelleher, 41, ditched digital engagement at Google Music in the Bay Area for Austin in 2017, after one too many South by Southwests. Inveterate record enthusiast, she found sanctuary in her new hood of audiophiles and got to know its Southern hospitality vendor, Kunz. Gold Rush Vinyl launched the following year at a time when only 16 vinyl presses operated worldwide.

One global virus later, that number’s tripled, with 10 more on the way in 2025.

“The hotel business, economically, was kind of the basis for Gold Rush Vinyl,” Kelleher says. “What I mean is that hotels have a finite capacity. You have so many rooms. And a lot of hotels will prioritize sold-out nights – push to sell out, but not think about the revenue per room, right?

“So my dad and I were talking about the vinyl problem and I said, ‘I should build a plant focused not on volume, but instead on quick-turnaround, high-quality work for people who really need it. It puts less stress on the machines, less stress on employees.’”

Under an enormous banner that once hung at the Armadillo World Headquarters, Gold Rush runs five presses, four stamping out vinyl and one pressing gold records. The main quartet, two of Swedish provenance and the others Canadian, winnowed down to a working duo last year and still managed to manufacture a quarter-million units. Each machine costs that same number, while my guide estimates costs for the cooling room around $2 million.

A vinyl listening room located behind the flower-laden lobby samples a representative from every Gold Rush batch five times before shipping out, and houses five copies of every pressing. Ten total employees manifest all the magic.

“I was always called the non-traditional MBA student,” Kelleher remarks. “It was almost said like an insult. In school, I thought maybe I would get out of music, largely, if I’m being honest, because when I looked ahead, there were no women in leadership roles in the music industry at that time and I could not see a blueprint for what my career would look like.”

She shares that her only sibling recently moved here and opened an agency called Corner Market Communications, which works with food and beverages. Caren played piccolo and Meghan went all-state with oboe and further as an opera singer.

“So I thought, ‘Okay, I should get into finance or tech,’ but I was one of only two students in my class of 900 who worked in the music industry and everyone knew I loved music. I got every music industry opportunity that came to Harvard and realized music’s a recession-proof industry.”

Ditto life insurance – a vocation Trey Watson inherited from his father.

W Capital Partners offices on Bee Caves Road in West Lake, product of a lucrative quarter century for the 51-year-old Baylor grad and father of three, who grew up in San Antonio and moved here in 1998 to buy and sell insurance. Even then, he recognized sales as a catalyst for collaboration.

“I don’t know that I’m ‘the money guy’ [in this deal] as much as somebody who communicates in a way people understand,” he offers when asked point-blank. “People like opportunity. They like cool things and being included in a community, whether that’s an investment deal or a record store.”

Former Gold Rush investor, Watson shipped the gold record machine here to the plant after recovering it from a bankruptcy cleanout of a photo archive deal netting him 25 million images. Kelleher and he, then, own a side hustle pressing 24-karat souvenirs for all comers and official awards for the RIAA. Vested in a decadelong country film documentary titled They Called Us Outlaws, he met Armadillo core Eddie Wilson, Mike Tolleson, and Hank Alrich.

Alrich owned Armadillo Records, a precursor to the famed Austin concert quonset hut that ran 1970-1980. Hypnotized by the dormant imprint’s iconic critter, designed by Jim Franklin for both label and club, Watson acquired the catalog (Shiva’s Headband, Kenneth Threadgill, the Cobras with Stevie Ray Vaughan). Alrich told one of his close friends, John Kunz.

“Armadillo Records was the model of me wanting to keep that connection to something back then and carry the baton forward in a new, improved way,” says Watson in the Gold Rush vinyl room. “That gave me the model with John Kunz, and I said the same thing to John after Caren continued to pepper him about maybe selling the business.

“Kevin [Wommack, local music impresario] helped me do the deal with Hank. When Kevin communicated to John basically how I treated Hank, I said, ‘John, I want to do the same thing. I want to buy Waterloo Records, I want Caren to be a part of it, and I want you. I’ll pay you your asking price, but I want you to keep a percentage of it because I need your input, your influence, your energy.’

“To preserve an Austin brand, you have to advance it and adapt with what’s happening.”

King Lear

Video killed the radio star only by degrees, but Napster (1999-2001) proved as cataclysmic to traditional album sales as the asteroid that wiped out dinosaurs. Industry sales flatlined for five years thereafter, which most businesses considered a win given what awaited them. Waterloo’s all-time sales peaked in 2005, yet from then until 2019, only “a couple years” did the store reach black.

“By 2017 or 2018, we were doing half the business we did in 2005,” reveals Kunz. “And our expenses – payroll, insurance, rent – were not half of what they’d been in 2005. When the recession hit [in 2000], we had a staff of 80, down from 90.

“Now I have a staff of 40.”

Kunz in front of Waterloo Records’ current home (600 N. Lamar) on Dec. 18, 2024 (Photo by David Brendan Hall)

Not coincidentally, perhaps, millennial file-sharing illuminated retail’s mortality.

“The vice president of Waterloo Records is Kathy Marcus, my wife,” begins Kunz. “My instructions to her were, ‘If I have a heart attack and die tomorrow, you now own Waterloo Records without having your key man running it anymore. You can put it out there publicly that it’s for sale and see what happens. Depending on where the lease is, you can have a retirement/going-out-of-business sale. And take care of everyone as best you can.’”

And what did Marcus, a photo editor and designer who worked in the Texas Monthly art department for over 20 years, say to that?

“We need a better plan.”

In fact, said plan began brewing a year previously, when a fellow music merchandiser, closing his own business, implored Kunz to distance himself from the industry.

“He was just like, ‘You know, for the success of your business and itself, you really need to be able to have a life outside of what you do.’ Well, my life outside of what I do – our lives, Kathy and myself – centers a whole lot around music and film anyway. As you well know, no matter how they intersect, it’s great to have your loves and hobbies and work all be the same.

“What I’m going to be doing now is semi-retiring,” he continues, acknowledging “a year’s worth” of untaken vacation. “And eventually, it’s going to be up to me when I want to work and how much I want to work, which is a pretty wonderful position to be in.”

Quite the moment in any lifetime.

“It’s probably more of a moment for Kathy [who’s already retired]. I’m having all kinds of empty-nester feelings. It’s bittersweet, but again, the dream was always …

“I mean, I don’t have children. Waterloo’s my baby. I want that child to live on and have a wonderful life.

“And … it’s my neighborhood record store!”

Kelleher, Kunz, and Watson at the new home of Waterloo Records (1105 N. Lamar) (Photo by David Brendan Hall)

Magma-Colored

“A band just picked up their vinyl.”

These words from Caren Kelleher as Watson and myself emerge from the Gold Rush listening room trigger a hard-stop in this OG vinylist.

“What band!?”

Everyone points at the white band van waiting in the loading dock: “Die Spitz!”

At South by Southwest 2023, the Austinites collapsed Red River microjoy Chess Club with punk dynamite. By Levitation 18 months later at Mohawk, the rising young quartet radiated megaton teen spirit – and zero vinyl at the merch table! Fan worship prevents looking directly at a star, but did bassist Kate Halter really just grant me my final vinyl wish of 2024?

“Magma-colored,” she grins, climbing into the driver’s seat.

Later, double EP long-player Teeth/The Revenge of Evangeline emulsifies my hi-fi.

“I joke, if you wanna have a big record collection, just start a factory,” Kelleher cracks. “It’ll only cost you a couple million dollars.”

Gold Rush Vinyl proves personally memorable, but Trey Watson can’t wait to top that at Waterloo, which plans on reopening in its new location in time for SXSW 2025. He teases the addition of two to three “experiential” rooms inside the store unseen anywhere.

“What you’ll see going on within this store is going to be different than anything Austin’s ever experienced,” Watson says. “John’s said to me on lots of occasions, ‘I wanted Waterloo Records to be a cultural music hub where people and community congregate and talk, and enjoy music.’

“He’s done that.

“But it’s still not the place it can be from a congregational perspective. My goal is to continue his message while creating an Austin flagship destination.”

Editor’s Note: A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that Caren Kelleher worked at Google Music in Los Angeles, not the Bay Area, and that Trey Watson’s father was a military veteran. The Chronicle regrets the error.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content