The discourse around Beyoncé’s latest album Cowboy Carter has been nothing short of astonishing. I’ve not only seen people reacting to the album, but I’ve seen people reacting to how other people are reacting to the album. I wouldn’t be surprised if there are also people reacting to the reactions. Regardless, I think one of the most fascinating things about this album has nothing to with the album itself but rather how the first single was announced, namely a Verizon commercial during the Super Bowl.

You might not think this is that strange. Global superstar partners with a billion-dollar corporation. Makes sense. But it got me thinking about how we are so far from the notion of caring about if a musician sells out that it’s not really even possible to do so anymore.

When Selling Out Sold Out

“If you aren’t honest about rock n’ roll,” Dan Zanes told the camera, “people can sense it.” Though I think Zanes is correct, the problem is that people didn’t think he was being honest.

Dan Zanes was a member of The Del Fuegos, a Boston-area band founded in 1980. In the handful of years after the group’s inception, they grew a sizable following and a reputation for making some of the best rootsy garage rock around. Then the Miller Brewing Company called.

Miller was working on an ad campaign based around the slogan “Miller’s made the American way.” The idea was to feature up-and-coming American bands in their ads to lend credence to the slogan. It may have worked for Miller, but it didn’t go well for The Del Fuegos.

The commercial aired in 1985 during Live Aid, the transcontinental benefit concert to raise funds to end the famine in Ethiopia. The Del Fuegos said the commercial immediately destroyed their credibility. They not only sold out, but it looked like they were cashing a check at the expense of those suffering in Africa. The band dissolved in the next few years.

You can dispute how important this ad was to The Del Fuego’s demise, but you can’t dispute that there was a perception that appearing in a commercial — that selling out — could lead to a band’s demise. While I was growing up in the 2000s, this idea existed, but it wasn’t as powerful. In fact, I can remember songs like Are You Gonna Be My Girl by Jet growing more popular after they were featured in an Apple commercial.

Don’t miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

So, what happened in the 20 years between The Del Fuegos and Jet such that our perception of what it means to be a musician and what it means sell out changed so dramatically? To understand this shift, I turned to Dan Ozzi.

After Green Day left the indie world for the mainstream, a flood of other punk bands were given the chance to follow … The support system these bands were being offered was enticing — proper studio accommodations, budgets to make music videos, and placements in malls and chain stores … But with this opportunity came a catch. The insular underground communities that had incubated these musicians were not about to let their scene be ransacked … The most ardent defenders of the underground grew militant toward those bold enough to break out of the communities that had birthed them. To toe the line, longtime fans found themselves turning their backs on bands to which they’d once been so devoted.

Using what Ozzi is describing, I think we can parse out two different strains of selling out:

-

Selling out is when an entity compromises their values or morals for a sum of money. An example of this would be Sex Pistol Johnny Lydon doing a commercial for Country Life butter.

-

Selling out is when an entity changes something about themselves in hopes of reaching a wider audience and subsequently making more money. An example of this would be Maroon 5 embracing a more pop-oriented sound after their guitar-driven debut Songs About Jane.

There is a good deal of overlap between these ideas, but they are distinct in that the second doesn’t involve moral complications as directly. Nevertheless, the through line is that someone is changing something about themselves for a big paycheck. Because that idea is so broad, you can apply it to both musical and non-musical scenarios. In fact, the non-musical uses go back much further. Long before you heard complaints of punk musicians selling out to major labels, you had writers in the early-1900s, like Thomas Watson, complaining of how “Local Western corruptionists sell out to Wall Street.”

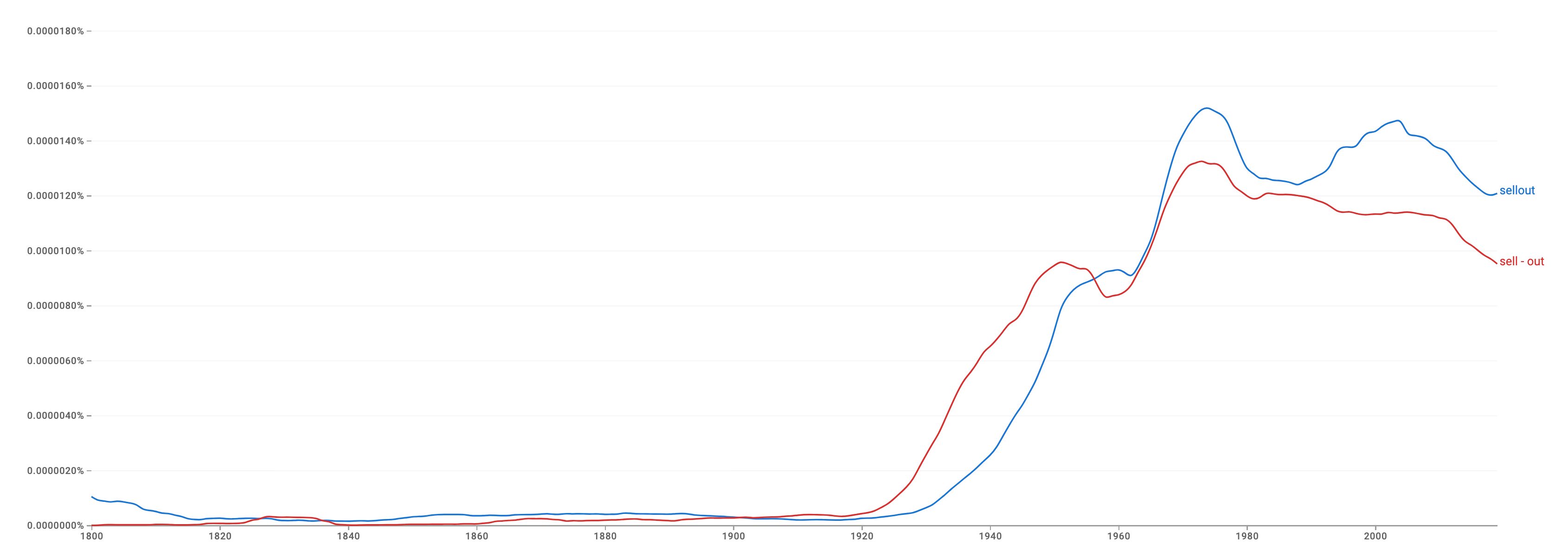

Google Ngram Viewer tracking appearances of the term “sellout” and “sell-out” across their corpus of books

When looking at Google’s Ngram Viewer, a tool that lets you track the usage of specific words and phrases across a large corpus of text, you see that the term “sellout” initially grew in usage between the 1920s and 1940s as consumer culture took hold. From 1960 to 2000, usage was relatively consistent before dropping in almost every year since 2003. While Google’s tool is going to capture the term in all contexts, we can look at what was going on in music when the decline began.

Music industry revenues rapidly contracted after the year 2000 as online piracy sites like Napster and LimeWire grew in popularity. Suddenly, there wasn’t as much money to go around. Artists and labels had to look for alternative revenue streams to compensate for declining record sales. Licensing your music to an advertisement was the perfect way to try to close the revenue gap.

According to critic Jessica Hopper, those declining revenues also led to layoffs at the labels. Many of those who lost their jobs ended up in advertising and marketing. Licensing your music for an ad not only made economic sense, but it also felt less shady given that you might be working with an old friend.

But why hasn’t the concept of selling out returned now that industry revenues are increasing in the streaming age? I think it largely has to do with social media. In the social media age, labels are waiting for artists to prove that they have a reliable audience before signing them. Again, if a label isn’t going to cut you a check, you need other income to survive.

Furthermore, a large part of the idea behind social media is based on selling out. If you aren’t willing to chase virality, then you aren’t doing it correctly. When an entire generation of artists is raised with that notion etched into their brains, it’s hard to be disgusted by the idea of selling out, let alone even understand what it means.

And the term really has lost meaning in the last few decades. By 2013, the term was so foreign that Gawker felt the need to define it when writing an article on the topic: “Once upon a time not so long ago, there was an idea: that some things in this world should be able to exist free from the influence of money—that these things should be done because of their own intrinsic value.” What that article is getting at is that selling out compromises your authenticity. You’ve chosen profits over honest art.

As I’ve noted multiple times, I’m increasingly skeptical of the notion of authenticity in music. That said, I think it would be beneficial if we questioned what is driving us to do something, artistic or not. It is not healthy to turn everything you do into a marketable product. And if you need a guide for how not to turn yourself into a product, remember Angus MacLise.

Angus MacLise was the original drummer of The Velvet Underground. When the group booked their first gig in December 1965, opening for The Myddle Class at a New Jersey high school, he quit in protest of the $75 they were going to be paid. The Velvet Underground, according to MacLise, was selling out.

MacLise was soon replaced by Marueen Tucker, thus rounding out The Velvet Underground’s classic line-up with Lou Reed, Sterling Morrison, and John Cale. Though I don’t think anybody would accuse The Velvet Underground of selling out, I think we could all use a little Angus MacLise in our lives to remind ourselves that we are people, not products.

Chris Dalla Riva is a musician who spends his days working at Audiomack, a popular music streaming service. He writes a weekly newsletter about popular music and data called Can’t Get Much Higher. His writing and research has also been featured by The Economist, NPR, and Business Insider. Can’t Get Much Higher is also available as a podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, and Substack.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content