“Pictures of Belonging” traces the careers of three female artists who flourished despite the U.S. government’s imprisonment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

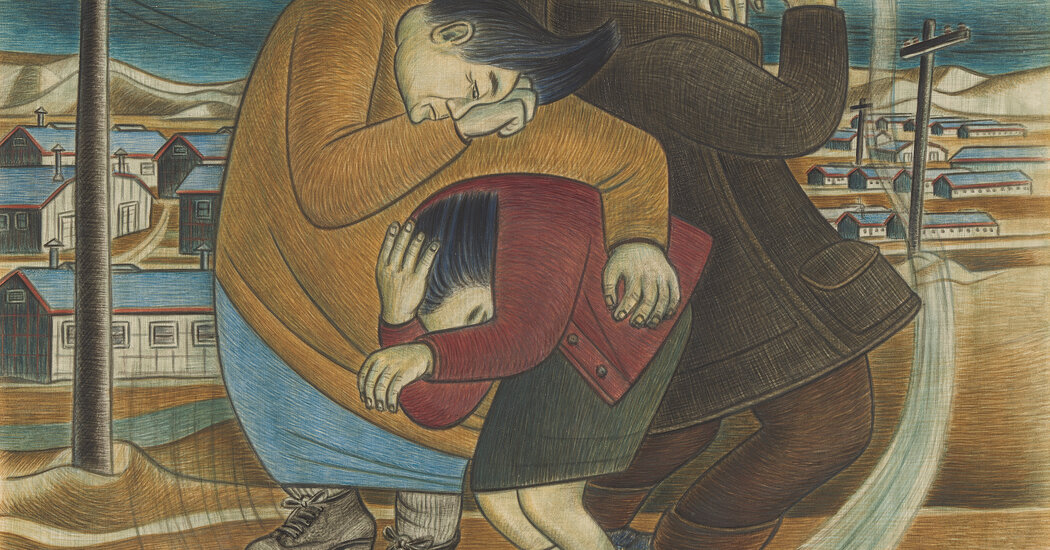

One of the indelible images in “Pictures of Belonging,” an exhibition of work by three female artists whose careers were impeded — but not snuffed out — by the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II, is Miné Okubo’s “Wind and Dust” from 1943. In it, a family shield their faces, and each other, from a sandstorm, huddled in a tight mass of interlocking bodies. Behind them, the desert is punctuated by barracks, a landscape of depressing sameness. You get the sense that these vulnerable figures are being battered not just by the weather, but by the world itself.

The watercolor was made at Topaz, in Utah, one the camps that Okubo was transferred to during the war. (They were referred to at the time by government officials as “concentration camps” or the more euphemistic “internment camps”; more recently, some historians have used the term “incarceration camps.”)

After President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066 on Feb. 19, 1942, on the heels of the bombing of Pearl Harbor, more than 120,000 Japanese Americans were removed from coastal areas, ostensibly for reasons of national security. They were forced to abandon their homes and possessions or sell them for a pittance, and to relocate to makeshift facilities in harsh conditions. About two-thirds of them were, like Okubo, American citizens.

“Pictures of Belonging,” organized by the curator and scholar ShiPu Wang in conjunction with the Japanese American National Museum in Los Angeles, and now on view at the Smithsonian American Art Museum in Washington, D.C., brings almost 100 works by Okubo, Hisako Hibi and Miki Hayakawa back into the frame of American art. Back into the frame, because these three women — Okubo, a second-generation Japanese American, and Hibi and Hayakawa, first-generation immigrants — were all acclaimed artists in a remarkably multicultural San Francisco art world before the war. Hibi and Okubo were incarcerated; Hayakawa’s parents were, too, but Hayakawa relocated to New Mexico to avoid that fate.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content