Five years ago, Muriel “Monik” Johnson watched her friend transform. Leah was a vibrant artist who loved going dancing. Though only 4-foot-9, she delighted in kissing Johnson’s face, starting at her chin, working clockwise to her forehead while she stood on her tippy toes, then found the ground again, fluttering back to the beginning.

When she was diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, Johnson took Leah to chemotherapy appointments for two years, but neither of them acknowledged the question hovering in the space between them. They watched mindless television. They reminisced about raising their children side-by-side in California.

So when Leah finally asked if she was dying, Johnson’s throat caught.

“I just could not utter the words,” she remembers. “I just held her hand tighter. I nodded and started crying and I said, ‘You have to come back to me. Come back and see me from the other side.’”

At this, Leah brightened. “I’m going to come back,” she said. “I’m going to come back as a butterfly.”

On Friday, Jan. 10, the opening reception of “Remember to Remember” will feature the artwork of women who have undergone a metamorphosis. During Arts Night Out at 33 Hawley, Available Potential Enterprises (A.P.E.) will bring together the works of Johnson, Emine Cichowski, and 40 artists from the Care Center. While Johnson is the only one whose medium is butterfly wings, all the women’s stories are rooted in transcendence.

After her dear friend Leah passed, Johnson’s daughter got pregnant. The early childhood educator and professional storyteller felt compelled to visit her girl in western Mass. Then she decided to stay, leaving behind her jobs and embracing her new identity as a grandmother.

In 2022 Johnson was with another close friend, Ann, when they discovered Magic Wings Butterfly Conservatory & Gardens in South Deerfield. As they navigated through 3,000 butterflies of all colors and sizes, a dead leaf butterfly landed on Johnson’s heart. Brown on the outside, it opened into a brilliant blue.

Johnson stared. A minute passed. Two minutes passed. Ann got out her phone and set the timer. While they walked around, the butterfly stayed put for 58 minutes.

“After three minutes I felt this vibration, this warmth and overwhelming comfort,” recalls Johnson. “It was Leah — she came back.”

In the gift shop, Johnson bought three packets of wings, which are collected after the butterflies in the conservatory die. She put them away for a year, and life went on. Her grandson was born. Her father died. A year after his passing, she spread out the wings on a white cutting board, and butterflies became her muse.

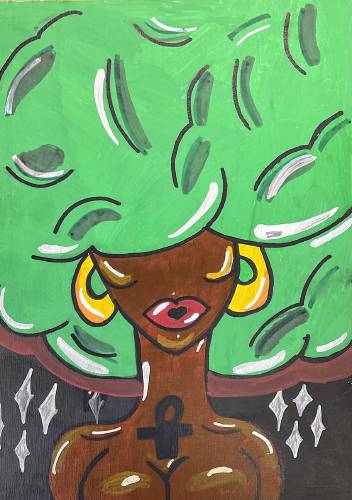

People started showing up in her dreams. Some were just flashes – her first was a woman with a big Afro that she recreated with butterfly wings – others had full stories, of slavery, of spirituality, of whole lives that lived in the corners of her mind.

She began sketching her ancestors and adorning them with wings. After making 20 pieces and stacking them on the floor, her husband insisted that she hang them on the walls. “I thought it was weird to hang my own art,” says Johnson, who considered herself a novice. But she obliged him, and when her daughter pushed her to show them, she reached out to A.P.E. The rest is history.

In a turn-of-the-century brick mansion in Holyoke, 200 mothers and low-income women, ages 16 to 24, return to high school. There is a day care on-site, as well as Bard Microcollege Holyoke for those who want to continue their education.

When students at the Care Center are introduced to art, says their instructor Lea Donnan, they are often hesitant to see themselves as artists: “The thing I hear the most is, ‘I don’t want to mess up.’ Part of what we do is make sure that students know they have a right to their ideas and self-expression. They’re here to expand a part of themselves that they may not have time and space for at home.”

“It’s like a chrysalis,” says Executive Director Oona Cook. “At the Care Center our students grow wings and prepare to fly.”

Student art adorns the walls of the nonprofit, reminding any skeptics of their potential. When Donnan told her students that A.P.E. was inviting them to be part of their upcoming show, the women were speechless, “which doesn’t happen a lot.” Then they were abuzz with ideas. One wanted to make art about postpartum depression. Another wanted to communicate that “it’s OK to not be OK.” This month, 40 artists will display their work in “Remember to Remember.”

“I love witnessing these women come into their power as students, as citizens and as mothers,” says Donnan. One of her students summed up it up best: “The future doesn’t know it yet,” she said, “but I’m coming.”

Her father had wanted a boy, but that didn’t stop her from dancing. While growing up in Gemlik, Turkey, Emine Cichowski learned quickly that art was resistance. So she moved her body freely. She learned how to sew and make her own dolls. “The girls were taught at an early age to make their dowry,” says Cichowski. “I used to tell my grandmother, ‘I’m not doing this to get married.’” She was doing it to feel alive.

Her grandmother, her father’s mother, was the first feminist she ever knew. After surviving World War I, she got married at 12 and her husband died eight years later, leaving her with three boys. “She said to the boys, ‘I will not get married and subject you to a stepdad,’” says Cichowski, who notes with pride that women in Turkey in the 1930s were not known for bucking the system. She worked at a hammam, or a Turkish bathhouse, which Cichowski remembers as a sort of sanctuary, a mosque-like structure where men came to relax in a steam room with marbled walls and tiled floors. Her grandmother also owned a small olive orchard, where she would take a 6-year-old Cichowski at picking time. They walked two miles to the orchard, and Cichowski knew they had arrived when they came upon the small fountain for those in need. “She would say, ‘Emine, look, the water is pouring here, we have the bread and the olives. This is riches.’”

After Cichowski became valedictorian of her class at an all-girls boarding school in Istanbul, her uncle, who taught at the University of Connecticut, recommended she attend UConn. When she came to America in 1968, she spoke very little English and was told by her uncle that she had to study science. She opted for the pharmacy program because he told her that it was “like cooking.”

Initially, “it was hell,” says Cichowski, who audited classes for six months and then continued full-time. In her second year she decided to marry, and in the third she had her daughter. During her fourth year, she interned at a pharmacy, where she discovered that the woman working the cash register was getting paid double her salary. When she asked her male boss why, he said, “Emine, what do you want? You are a woman and you are a foreigner.” She grabbed her bag and walked out, telling her husband that she would never work for anyone again. They opened their own apothecary in Mansfield, Connecticut, which they ran successfully until 1998, and at 50, Cichowski retired.

While she worked at the pharmacy, she had passed a local pottery shop one day and was inspired to take classes. But she never expected clay to become her muse. Her husband built her a studio, and she began spending whole days inside. “I immersed myself, I lost myself, and I realized that when I am doing what I love, I don’t even know where the time goes,” she says.

Cichowski’s favorite poet is Rumi, who believes that “the soul has no age.” Now in her 70s and a grandmother herself, she feels like she has come full circle.

“Creativity comes from my memory of childhood,” she says, “and making it alive again.”

“Remember to Remember” runs from Jan. 8 to Feb. 1 at 33 Hawley. The opening reception is on Jan. 10 from 5 to 8 p.m. For more information, visit apearts.org.

Melissa Karen Sances lives in western Mass., where she writes stories about extraordinary people. Reach her at melissaksances@gmail.com.

More Arts for you

By using this site, you agree with our use of cookies to personalize your experience, measure ads and monitor how our site works to improve it for our users

Copyright © 2016 to 2024 by H.S. Gere & Sons, Inc. All rights reserved.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content