In January, several industry insiders predicted there would be more attention paid this year to Indigenous and Native art. That month, Phillips was gearing up to hold “New Terrains,” its first selling exhibition of contemporary Indigenous and Native art at its New York headquarters. Quickly, it became apparent that the predictions made around the time of the Phillips show were correct. Later that month, the Venice Biennale would announce its artist list for the main exhibition, “Foreigners Everywhere,” which included numerous Indigenous artists.

Now, 2024 is nearly complete, and further proof that Indigenous art is on the rise has arrived in museums, auction houses, and galleries. Jeffrey Gibson (Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians/Cherokee), the artist who represented the United States at the Venice Biennale, got representation with Hauser & Wirth. Emmi Whitehorse, a Diné painter who showed in the Biennale’s main exhibition, gained a new auction record at Phillips, where one of her paintings sold for over $117,000—nearly nine times its high estimate. A retrospective for Aboriginal painter Emily Kam Kngwarray continued to travel Australia, and even resulted in the late artist’s addition to Pace’s roster.

Emmi Whitehorse (Diné), Canyon Lake I, 2001. It sold for $177,8000 on a high estimate of $18,000. Courtesy of Phillips.

Jean Bourbon

It’s clear that Indigenous art is gaining more mainstream notice than ever before. But, some dealers, art advisers, and auction house executives said the impact of all this on the market remains uncertain.

Multiple sources said the Venice Biennale had a significant impact in bringing global attention to Indigenous artists.

“There were Native artists from the United States, but there were Indigenous artists from Indonesia, from Africa, and especially from Latin America, because that is Adriano’s expertise,” Mary Sabbatino, vice-president and partner of Galerie Lelong, told ARTnews, referring to Biennale curator Adriano Pedrosa. “I think that will have a ripple effect for 10 years.”

Along with Whitehorse, the main exhibition included Brazilian Yanomami artists Joseca Mokahesi and André Taniki; Indigenous Australian artists Marlene Gilson and Naminapu Maymuru-White; Māori artists Sandy Adsett and Selwyn Wilson; and Native American artist Kay Walkingstick (Cherokee).

“I met so many new people as a result of them having seen those pieces,” gallerist Garth Greenan, who represents Whitehorse and a significant number of other Indigenous and Native artists at his eponymous New York gallery, told ARTnews.

The Biennale also awarded its top prizes to the four Māori women of the Mataaho Collective and Archie Moore (Kamilaroi/Bigambul) for the Australia Pavillion.

Artist Nicholas Galanin (Tlingít/Unangax̂) told ARTnews that, while the work by Indigenous artists featured at the Biennale was amazing, he was not surprised by its inclusion. “I’ve been able to cross paths and meet so many incredible artists throughout the last 25 years of plus, or whatever, how long I’ve been doing this,” he told ARTnews. “I’ve known these artists and their work, and I’ve always known it’s been great.”

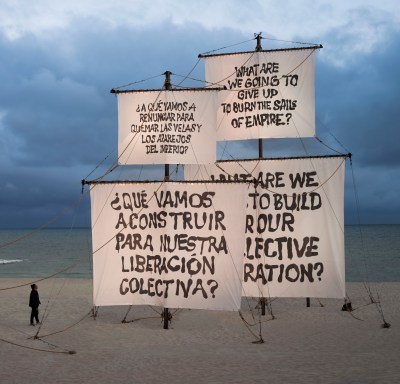

Galanin also had a banner year, with work featured in the Phillips sale, solo exhibitions at the Baltimore Museum of Art and Peter Blum Gallery in New York, and a Guggenheim fellowship. Earlier this month, during Art Basel Miami Beach, Galanin unveiled a newly commissioned installation on Faena Beach near the fair.

Nicholas Galanin, Seletega, 2024. Photography by Oriol Tarridas

ORIOL TARRIDAS

Indigenous and Native artists also figured prominently in PST ART, the recurring initiative funded by the Getty Foundation, in which over 70 California institutions stage exhibitions around a single theme. For this year’s edition, “Art & Science Collide,” the Los Angles County Museum of Art, the Fowler Museum at UCLA, and the Autry Museum of the American West all staged shows centered on Indigenous artists. Numerous other shows included Indigenous works.

Fragmentation at Auction and Private Sales

Even with the significant rise in visibility, interest in works by Indigenous artists has been fragmented this year like the rest of the art market. While new auction records were set for Whitehorse and Kent Monkman (Cree) in May at Phillips, Gibson’s 2014 sculpture Always After Now failed to sell during his evening sale debut that same month at Sotheby’s.

For Phillips, the “New Terrains” exhibition in January and a Monkman sale via its direct-from-artist DropShop platform prompted more appraisal inquiries and interest, but the house has been offered far fewer consignments than expected for top-level artworks in the category, according to deputy chairman and head of private sales, Miety Heiden.

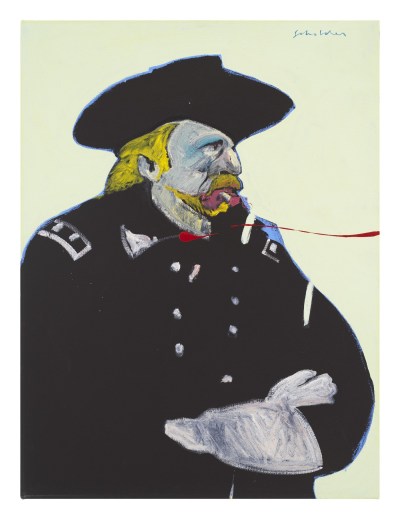

“The answer we got is, ‘If we sell it now, we don’t get it back again,’ which I think is absolutely true,” Heiden told ARTnews. “We keep on looking for a great Fritz Scholder, a great [George] Morrison, but they’re incredibly hard to find, and people are not very willing to sell.”

Courtesy of the Estate of Fritz Scholder, Garth Greenan Gallery, New York, and LewAllen Galleries, Sante Fe.

Another complicating factor to growing the appeal of this category is the subject matter broached by many Indigenous artists, who have historically dealt head-on with land ownership, colonialism, and racism, often in conceptual ways. “It’s more complex often, given the historical references, given the hardship they went through as Indigenous artists in their communities [and] how they got marginalized,” art adviser and gallerist Thomas Stauffer of the Zurich-based Gerber & Stauffer Fine Arts told ARTnews.

Greenan was not surprised Phillips didn’t experience a booming market in private sales and auction consignments after its selling exhibition. “It’s not about a fast, immediate return,” he said. “It’s about inclusion and a kind of holistic embrace by institutions, private museums, galleries, etc., and by art history in general.”

Several sources echoed Heiden, noting the growth in demand for mid-career and historic artists such as Jaune Quick-to-See Smith (Confederated Salish/Kootenai tribes), Schoulder (Luiseño), Morrison (Ojibwe), T.C. Cannon (Kiowa/Caddo), Oscar Howe (Yanktonai/Dakota), Andrea Carlson (Ojibwe), Dyani White Hawk (Sicangu Lakota), Rose Simpson (Santa Clara Pueblo) and Galanin.

“I used to be able to buy George Morrison [works] at auction for nothing all the time, and now I can’t,” Zach Feuer, cofounder of the Forge Project and director of the Gochman Family Collection, told ARTnews. The competition for masks by Beau Dick (Kwakwaka’wakw) has also noticeably risen. “I got outbid on two of them this month, so I am definitely getting beat out on that,” Feuer said.

Artist Tony Abeyta (Navajo), one of the three co-curators of “New Terrains,” said some of the works sold after the Phillips sale, which also prompted new commissions and representation for several participating artists. “For me, that’s what I loved about it,” he said. “We were able to make connections with New York and Indigenous artists throughout the country that might not have had that opportunity.”

Several Indigenous artists had their first shows in New York this year, including Ishi Glinsky (Tohono O’odham Nation) at PPOW, Rachel Martin (Tlingít) at Hannah Traore Gallery and Teresa Baker (Mandan/Hidatsa) at Broadway. “I think all of those shows did really well,” Feuer said.

Greenan said he observed greater institutional interest for artists he represents, including Smith, Whitehorse, multimedia artist Cannupa Hanska Luger (Mandan/Hidatsa/Arikara/Lakota), and weaver Melissa Cody (Navajo).

“There’s been so much steady institutional activity, because that’s where I think the biggest edict is,” Greenan said, noting that sales to individual collectors interested in filling gaps in existing collections of American and contemporary art have also been steady as well.

And, at Art Basel Miami Beach this year, Sabbatino noticed the large booth for Greenan’s gallery in a prominent location. The presentation included works by Cody, Luger, Whitehouse, and Quick-to-See among others.

“I think that is an indication that those artists are not marginal or a number of them are considered important artists to show, not in a niche fair, but in a global, central art fair—a Basel fair,” Sabbatino said.

The booth for Garth Greenan Gallery at this year’s Art Basel Miami Beach with Cannupa Hanska Luger’s sculpture Midéegaadi: Lightning Bison (2022) in the center. Photo by Mark Blower, courtesy of Garth Greenan Gallery.

An Ongoing Process

Artists who are not straight white males are not so immediately accepted and integrated into museums, galleries, and art history textbooks, which means that Indigenous artists face a difficult battle. Some artists said they were aware of the challenges involved.

“All I know is it’s an ongoing process that takes centuries to fulfill,” filmmaker, artist, and curator Dana Claxton (Wood Mountain Lakota First Nation) told ARTnews.

In between milestones like auction records, major institutional acquisitions, biennial inclusions, and installations at major fairs, Indigenous artists like Galanin also have simpler goals, like helping pay for the college tuition of his six children. “My goal is to be able to put them through at least some form of higher education,” he said.

As the profile and interest in Indigenous artists continues to grow, Abeyta has also noticed more young, with contemporary Indigenous artists feeling encouraged to be experimental in how they think, create, and collaborate. “I’m more interested in that than hearing about one artist who’s selling something for $1.2 million,” Abeyta said.

This post was originally published on this site be sure to check out more of their content